Chapter from Nick Flynn’s extraordinarily authentic and poetic memoir, The Ticking Is the Bomb:

For those few years when I worked in New York City public schools as an itinerant poet—Crown Heights, Harlem, the South Bronx—I’d lug a satchel heavy with books on the train every morning. Much of what I taught was directed toward finding out what the students saw every day. It was a way to honor their lives, which isn’t generally taught in public schools.

For those few years when I worked in New York City public schools as an itinerant poet—Crown Heights, Harlem, the South Bronx—I’d lug a satchel heavy with books on the train every morning. Much of what I taught was directed toward finding out what the students saw every day. It was a way to honor their lives, which isn’t generally taught in public schools.

The beginning exercises were very simple: Tell me one thing you saw on the way into school this morning. Tell me one thing you saw last night when you got home. Describe something you see every day, describe something you saw only once and wondered about from then on. Tell me a dream, tell me a story someone told you, tell me something you’ve never told anyone else before. No one, in school at least, had ever asked them what their lives were like, no one had asked them to tell about their days. In this sense it felt like a radical act. I tried to imagine what might happen if each of them knew how important their lives were.

In the schools I’d visit, I’d sometimes pick up a discarded sheet of paper from the hallway floor, something a student had written in his notebook and then torn out. Sometimes, I could tell that he’d been given an assignment, and that he’d tried to fulfill it, and by tearing it out it was clear that he felt he had somehow failed.

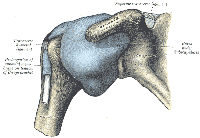

Out of all the ephemera I’ve bent down to collect from black and green elementary school linoleum floors over the years, one has stayed with me. Likely it was part of a research paper, likely for biology. It started with a general statement, which was, I imagine, meant to be followed by supporting facts. The sentence, neatly printed on the first line, was this: All  living things have shoulders—after this there was nothing, not even a period, as if even as he was writing it he realized something was wrong, that he would never be able to support what he was only beginning to say, that no facts would ever justify it.

living things have shoulders—after this there was nothing, not even a period, as if even as he was writing it he realized something was wrong, that he would never be able to support what he was only beginning to say, that no facts would ever justify it.

All living things have shoulders—the first word is pure energy, the sweeping “All,” followed by the heartbeat of “living”—who wouldn’t be filled with hope having found this beginning? Then the drift begins, into uncertainty—”things”—a small misstep, not so grave that it couldn’t be righted, but it won’t be easy. Now something has to be said, some conclusion, I can almost hear the teacher, I can almost see what she has written on the blackboard—”Go from the general to the specific”—and what could be more general than “All living things,” and what could be more specific than “shoulders”? He reads it over once and knows it can never be reconciled, and so it is banished from his notebook.

All living things have shoulders—this one line, I have carried it with me since, I have tried to write a poem from it over and over, and failed, over and over. I have now come to believe that it already is a poem.

All living things have shoulders. Period. The end. A poem.

"I would suggest that the notion that there is this immaterial soul—which some people might believe departs the body at death and some people might believe takes on another body in a future life—that’s an illusion, I think. Other people take a different line on this. Other people do believe there is self-stuff or soul-stuff somewhere. But the question is, Where is it? How would you when you found it? What would you be looking for? I have no idea what you’d expect to find…I have the same body, more or less, from day-to-day. I look in the mirror and it’s me. But essentially what I tell you, if you were to ask me about myself, I tell you a story…The extended self, which is what we normally think of when we think about ourselves, is really a story. It's the story of what's happened to a body over time."

"I would suggest that the notion that there is this immaterial soul—which some people might believe departs the body at death and some people might believe takes on another body in a future life—that’s an illusion, I think. Other people take a different line on this. Other people do believe there is self-stuff or soul-stuff somewhere. But the question is, Where is it? How would you when you found it? What would you be looking for? I have no idea what you’d expect to find…I have the same body, more or less, from day-to-day. I look in the mirror and it’s me. But essentially what I tell you, if you were to ask me about myself, I tell you a story…The extended self, which is what we normally think of when we think about ourselves, is really a story. It's the story of what's happened to a body over time."

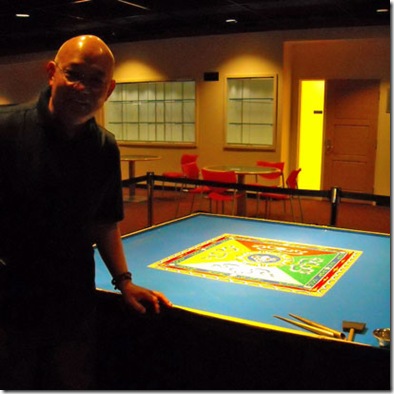

“We come to meditation to learn how not to act out the habitual tendencies we generally live by, those actions that create suffering for ourselves and others, and get us into so much trouble. Doing nothing does not mean going to sleep, but it does mean resting—resting the mind by being present to whatever is happening in the moment, without adding on the effort of attempting to control it. Doing nothing means unplugging from the compulsion to always keep ourselves busy, the habit of shielding ourselves from certain feelings, the tension of trying to manipulate our experience before we even fully acknowledge what that experience is.”

“We come to meditation to learn how not to act out the habitual tendencies we generally live by, those actions that create suffering for ourselves and others, and get us into so much trouble. Doing nothing does not mean going to sleep, but it does mean resting—resting the mind by being present to whatever is happening in the moment, without adding on the effort of attempting to control it. Doing nothing means unplugging from the compulsion to always keep ourselves busy, the habit of shielding ourselves from certain feelings, the tension of trying to manipulate our experience before we even fully acknowledge what that experience is.”

For those few years when I worked in New York City public schools as an itinerant poet—Crown Heights, Harlem, the South Bronx—I’d lug a satchel heavy with books on the train every morning. Much of what I taught was directed toward finding out what the students saw every day. It was a way to honor their lives, which isn’t generally taught in public schools.

For those few years when I worked in New York City public schools as an itinerant poet—Crown Heights, Harlem, the South Bronx—I’d lug a satchel heavy with books on the train every morning. Much of what I taught was directed toward finding out what the students saw every day. It was a way to honor their lives, which isn’t generally taught in public schools.

“…never, ever do anything to deprive a human being of their dignity in work, in life. Always praise in public and criticize in private. You might be tempted, for example, when you’re letting someone go, to say something that would diminish the value of their work. Don’t ever do that.

“…never, ever do anything to deprive a human being of their dignity in work, in life. Always praise in public and criticize in private. You might be tempted, for example, when you’re letting someone go, to say something that would diminish the value of their work. Don’t ever do that.

"If I feel really bad about myself, if I don't like myself, how many people are there in here? Which one is it that doesn't like the other one? Isn't there a sense of superiority? When I say, I'm such a schmuck, isn't the person who's thinking that a little bit better than the schmuck that he just judged? So how many people are there in there? It looks like at least two. When I think, Oh, I'm such a jerk, selfish person, hot-tempered person—whatever derogative comment we make about ourselves—it seems to me that it is a classic instance of it-ifying oneself. Just turning oneself into an unpleasant object from a superior vantage point and then looking down on oneself as that's the one I don't like.

"If I feel really bad about myself, if I don't like myself, how many people are there in here? Which one is it that doesn't like the other one? Isn't there a sense of superiority? When I say, I'm such a schmuck, isn't the person who's thinking that a little bit better than the schmuck that he just judged? So how many people are there in there? It looks like at least two. When I think, Oh, I'm such a jerk, selfish person, hot-tempered person—whatever derogative comment we make about ourselves—it seems to me that it is a classic instance of it-ifying oneself. Just turning oneself into an unpleasant object from a superior vantage point and then looking down on oneself as that's the one I don't like.  But it happens not only for self-loathing, low self-esteem, lack of self-worth and so forth, but on some occasions some people feel pretty good about themselves: self-infatuation. Looking into the mirror and saying, Looking good! I am really something. And now there's one more it and this is a pleasant it. We're applauding the it as if we're watching a show. So we can it-ify, objectify, in an agreeable fashion, in which case we become objects of attachment for ourselves. We can be also objects of aversion for ourselves. And on other occasions, we can simply say, Man, you're a boring person. I don't really care much about you one way or another. So one more it-ifying.”

But it happens not only for self-loathing, low self-esteem, lack of self-worth and so forth, but on some occasions some people feel pretty good about themselves: self-infatuation. Looking into the mirror and saying, Looking good! I am really something. And now there's one more it and this is a pleasant it. We're applauding the it as if we're watching a show. So we can it-ify, objectify, in an agreeable fashion, in which case we become objects of attachment for ourselves. We can be also objects of aversion for ourselves. And on other occasions, we can simply say, Man, you're a boring person. I don't really care much about you one way or another. So one more it-ifying.”

“The support, the privilege, really comes from having two parents that said and believed that I could do anything. That support didn't come in the form of a check. That support came in the form of love and nurturing and respect for us finding our way, falling down, figuring out how to get up ourselves…I learned more in those [difficult] times about myself and my resiliency than I ever would have if I'd had a pile of money and I could have glided through life. I honestly feel that it is an act of love to say, 'I believe in you as my child, and you don't need my help.' "

“The support, the privilege, really comes from having two parents that said and believed that I could do anything. That support didn't come in the form of a check. That support came in the form of love and nurturing and respect for us finding our way, falling down, figuring out how to get up ourselves…I learned more in those [difficult] times about myself and my resiliency than I ever would have if I'd had a pile of money and I could have glided through life. I honestly feel that it is an act of love to say, 'I believe in you as my child, and you don't need my help.' " "For me, the main thing that I found after my three-year quest was meditation. Meditation was a real major revelation for me, not only for my life but for my sleep. It really helped calm me down. So I think if you can do any type of relaxation exercises, if you can practice breathing, I think that if you can do it, it's far more beneficial than going the pharmaceutical route.”

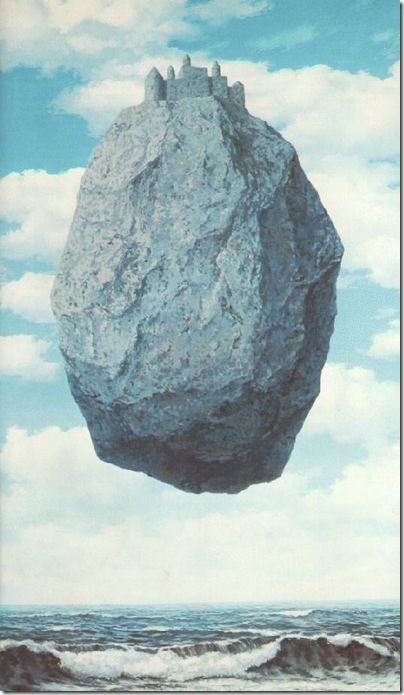

"For me, the main thing that I found after my three-year quest was meditation. Meditation was a real major revelation for me, not only for my life but for my sleep. It really helped calm me down. So I think if you can do any type of relaxation exercises, if you can practice breathing, I think that if you can do it, it's far more beneficial than going the pharmaceutical route.” Here’s a secret: Everyone, if they live long enough, will lose their way at some point. You will lose your way, you will wake up one morning and find yourself lost. This is a hard, simple truth. If it hasn’t happened to you yet consider yourself lucky. When it does, when one day you look around and nothing is recognizable, when you find yourself alone in a dark wood having lost the way, you may find it easier to blame someone else—an errant lover, a missing father, a bad childhood. Or it may be easier to blame the map you were given—folded too many times, out of date, tiny print. You can shake your fist at the sky, call it fate, karma, bad luck, and sometimes it is. But, for the most part, if you are honest, you will only be able to blame yourself. Life can, of course, blindside you, yet often as not we choose to be blind—agency, some call it. If you’re lucky you’ll remember a story you heard as a child, the trick of leaving a trail of breadcrumbs, the idea being that after whatever it is that is going to happen in those woods has happened, you can then retrace your steps, find your way back out. But no one said you wouldn’t be changed, by the hours, the years, spent wandering those woods.

Here’s a secret: Everyone, if they live long enough, will lose their way at some point. You will lose your way, you will wake up one morning and find yourself lost. This is a hard, simple truth. If it hasn’t happened to you yet consider yourself lucky. When it does, when one day you look around and nothing is recognizable, when you find yourself alone in a dark wood having lost the way, you may find it easier to blame someone else—an errant lover, a missing father, a bad childhood. Or it may be easier to blame the map you were given—folded too many times, out of date, tiny print. You can shake your fist at the sky, call it fate, karma, bad luck, and sometimes it is. But, for the most part, if you are honest, you will only be able to blame yourself. Life can, of course, blindside you, yet often as not we choose to be blind—agency, some call it. If you’re lucky you’ll remember a story you heard as a child, the trick of leaving a trail of breadcrumbs, the idea being that after whatever it is that is going to happen in those woods has happened, you can then retrace your steps, find your way back out. But no one said you wouldn’t be changed, by the hours, the years, spent wandering those woods.