Reasoning Is Suffused With Emotion

Excerpt from “The Science of Why We Don’t Believe Science,” by Chris Mooney, Mother Jones, April 18, 2011:

The theory of motivated reasoning builds on a key insight of modern neuroscience. Reasoning is actually suffused with emotion (or what researchers often call "affect"). Not only are the two inseparable, but our positive or negative feelings about people, things, and ideas arise much more rapidly than our conscious thoughts, in a matter of milliseconds—fast enough to detect with an EEG device, but long before we're aware of it. That shouldn't be surprising: Evolution required us to react very quickly to stimuli in our environment. It's a "basic human survival skill," explains political scientist Arthur Lupia of the University of Michigan. We push threatening information away; we pull friendly information close. We apply fight-or-flight reflexes not only to predators, but to data itself.

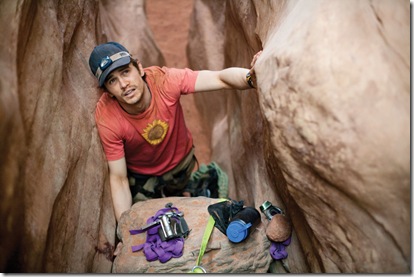

Illustration by Jonathon Rosen |

We're not driven only by emotions, of course—we also reason, deliberate. But reasoning comes later, works slower—and even then, it doesn't take place in an emotional vacuum. Rather, our quick-fire emotions can set us on a course of thinking that's highly biased, especially on topics we care a great deal about.

Consider a person who has heard about a scientific discovery that deeply challenges her belief in divine creation—a new hominid, say, that confirms our evolutionary origins. What happens next, explains political scientist Charles Taber of Stony Brook University, is a subconscious negative response to the new information—and that response, in turn, guides the type of memories and associations formed in the conscious mind. "They retrieve thoughts that are consistent with their previous beliefs," says Taber, "and that will lead them to build an argument and challenge what they're hearing."

In other words, when we think we're reasoning, we may instead be rationalizing. Or to use an analogy offered by University of Virginia psychologist Jonathan Haidt: We may think we're being scientists, but we're actually being lawyers. Our "reasoning" is a means to a predetermined end—winning our "case"—and is shot through with biases. They include "confirmation bias," in which we give greater heed to evidence and arguments that bolster our beliefs, and "disconfirmation bias," in which we expend disproportionate energy trying to debunk or refute views and arguments that we find uncongenial.

That's a lot of jargon, but we all understand these mechanisms when it comes to interpersonal relationships. If I don't want to believe that my spouse is being unfaithful, or that my child is a bully, I can go to great lengths to explain away behavior that seems obvious to everybody else—everybody who isn't too emotionally invested to accept it, anyway. That's not to suggest that we aren't also motivated to perceive the world accurately—we are. Or that we never change our minds—we do. It's just that we have other important goals besides accuracy—including identity affirmation and protecting one's sense of self—and often those make us highly resistant to changing our beliefs when the facts say we should.

The mind can’t fathom that there can be a true intelligence, a transcendent intelligence, that isn’t the product and outcome of thought and conceptual understanding. It can’t fathom that there could be wisdom that’s not going to come at you in the form of thoughts, in the form of acquired and accumulated knowledge.

The mind can’t fathom that there can be a true intelligence, a transcendent intelligence, that isn’t the product and outcome of thought and conceptual understanding. It can’t fathom that there could be wisdom that’s not going to come at you in the form of thoughts, in the form of acquired and accumulated knowledge.

SOCRATES: He then who sees some one thing, sees something which is?

SOCRATES: He then who sees some one thing, sees something which is?  The purpose of mindfulness…is to help us detach ourselves from the ego by observing the way our minds work. You might find it helpful to learn more about the neurological makeup of the brain and the way that meditation can enhance your sense of peace and interior well-being…but this is not essential. Practice is more important than theory, and you will find that it is possible to work on your mental processes just as you work out in the gym to enhance your physical fitness.

The purpose of mindfulness…is to help us detach ourselves from the ego by observing the way our minds work. You might find it helpful to learn more about the neurological makeup of the brain and the way that meditation can enhance your sense of peace and interior well-being…but this is not essential. Practice is more important than theory, and you will find that it is possible to work on your mental processes just as you work out in the gym to enhance your physical fitness.

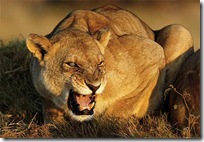

to propagate her genes, thus fostering a kind of protective alarmism in her descendants. Another might think, “There’s always some kind of rustling in the tall grass, it’s probably the wind,” and keep on grooming. If he guesses wrong, the downside is being eaten by the lion. Thus, no offspring and no propagation of the “don’t worry, be happy” genes.

to propagate her genes, thus fostering a kind of protective alarmism in her descendants. Another might think, “There’s always some kind of rustling in the tall grass, it’s probably the wind,” and keep on grooming. If he guesses wrong, the downside is being eaten by the lion. Thus, no offspring and no propagation of the “don’t worry, be happy” genes.

We’re often quite sure about what other people need to do, how they should live, and whom they should be with. We have 20/20 vision about others, but not about ourselves. When you do

We’re often quite sure about what other people need to do, how they should live, and whom they should be with. We have 20/20 vision about others, but not about ourselves. When you do

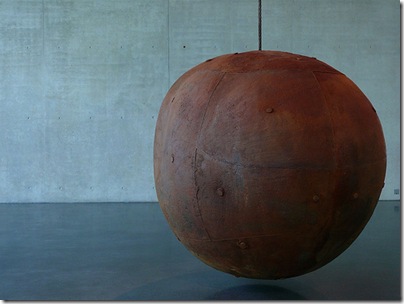

Learning to See give strength to the artist’s conception of inner vision, the dualities evoked by the installation at Charleston are subservient to a sense of passage towards expansiveness. The emotional depth of the work can be ascribed to its refusal to exclude either the particular or the universal: it encompasses both historical specificity and a sense of shared human experience. In formal terms, this is achieved by the undermining of the Modernist notion of the self-referential object. While each of the elements of the installation can be separately contemplated, they are most meaningful when perceived as parts of a larger whole. In that sense, they are like parts of a body.

Learning to See give strength to the artist’s conception of inner vision, the dualities evoked by the installation at Charleston are subservient to a sense of passage towards expansiveness. The emotional depth of the work can be ascribed to its refusal to exclude either the particular or the universal: it encompasses both historical specificity and a sense of shared human experience. In formal terms, this is achieved by the undermining of the Modernist notion of the self-referential object. While each of the elements of the installation can be separately contemplated, they are most meaningful when perceived as parts of a larger whole. In that sense, they are like parts of a body.  Just as the day could use another hour,

Just as the day could use another hour,

Heart

Heart