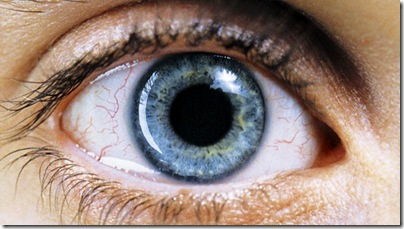

Seeing Clearly What Is Happening

Mark Williams from “Mindfulness is Happiness,” WealthWise Magazine, May 16, 2011:

Mindfulness simply means being aware — seeing clearly what is happening in our minds and in the world, from moment to moment, bringing a sense of kindness to our experience rather than getting caught in judging it.

Mindfulness simply means being aware — seeing clearly what is happening in our minds and in the world, from moment to moment, bringing a sense of kindness to our experience rather than getting caught in judging it.

The methods used to cultivate mindfulness were first recorded over two thousand years ago. It has long been central to wisdom traditions in Asia, particularly the Buddhist tradition, but the art of cultivating inner silence has been a central part of all religious traditions across the ages.

Mindfulness meditation is a secular form of this tradition that anyone can learn. It trains us to pay deliberate attention to our experience, both external and internal. We learn to focus on what is happening from moment to moment with full intention and without judgment. Mindfulness is the awareness that emerges through such training, and the skill of developing and sustaining that awareness.

Modern mindfulness-based approaches in healthcare began in the USA. From the late 1970s, Jon Kabat-Zinn’s pioneering research into Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR1) found remarkable effects on chronic pain and stress. With colleagues John Teasdale and Zindel Segal, we have reasoned that mindfulness training might have powerful effects in preventing future recurrence of depression, even if taught when people were well.

To test this hypothesis, we have created the 8-week Mindfulness-Based Cognitive therapy program. Six research trials have evaluated the power of MBCT to prevent depression. The results are striking. In the most seriously ill patients – those with three or more previous episodes of depression, MBCT reduces the recurrence rate over 12 months by 40-50% compared with the usual care, and has proved to be as effective as maintenance antidepressants in preventing new episodes of depression.

…Mindfulness is “skills training” rather than traditional type of therapy, so anyone can try it without feeling that they have to go over old ground, or talk through their problems yet again. Those already in therapy report finding treatment easier if they are more able to be mindful, and to see their thoughts and feelings with greater distance and perspective.

The mind can’t fathom that there can be a true intelligence, a transcendent intelligence, that isn’t the product and outcome of thought and conceptual understanding. It can’t fathom that there could be wisdom that’s not going to come at you in the form of thoughts, in the form of acquired and accumulated knowledge.

The mind can’t fathom that there can be a true intelligence, a transcendent intelligence, that isn’t the product and outcome of thought and conceptual understanding. It can’t fathom that there could be wisdom that’s not going to come at you in the form of thoughts, in the form of acquired and accumulated knowledge.

Who am I? That is a simple question, yet it is one without a simple answer. I am many things—and I am one thing. But I am not a thing that is just lying around somewhere, like a pen, or a toaster, or a housewife. That is for sure. I am much more than that. I am a living, breathing thing, a thing that can draw with a pen and toast with a toaster and chat with a housewife, who is sitting on a couch eating toast. And still, I am much more.

Who am I? That is a simple question, yet it is one without a simple answer. I am many things—and I am one thing. But I am not a thing that is just lying around somewhere, like a pen, or a toaster, or a housewife. That is for sure. I am much more than that. I am a living, breathing thing, a thing that can draw with a pen and toast with a toaster and chat with a housewife, who is sitting on a couch eating toast. And still, I am much more. Excerpt from "

Excerpt from "

More and more businesses and managers are becoming interested in meditation, according to

More and more businesses and managers are becoming interested in meditation, according to

brain, and can cause physical changes to the structure of regions involved in learning, memory, emotion regulation and cognitive processing.

brain, and can cause physical changes to the structure of regions involved in learning, memory, emotion regulation and cognitive processing.