Excerpts from Antony Gormley (Contemporary Artists) by John Hutchinson, E.H. Gombrich, and Lela B. Njatin:

To Meister Eckhart, art was religion and religion art. Artistic form, in his view, was a revelation of essence, a kind of revelation that is both living and active. “Work,” he wrote, “comes from the outward and from the inner man, but the innermost man takes no part in it. In making a thing the very innermost self of a man comes into outwardness.”

…

Much of Antony Gormley’s art is based on his understanding of Western and Eastern spiritual traditions, and his work resonates when it is placed in this context. Like Eckhart — or, indeed like Joseph Beuys — Gormley believes that the artist is not a special kind of man, but that every man is a special kind of artist…He works with “types,” with universals, and yet he roots his work in subjective experience…But what concerns Gormley more than anything else, is the paradoxical manner in which man, while containing infinite space, is also contained by it…His sculpture deals with what he sees as the “deep space” of the interior body, yet he is also concerned with “touch as gravity” and “gravity as the attraction that binds us to the earth.” Its key strength, perhaps, lies in the artist’s determination to accept nothing until is has been lived and internalized. Gormley’s work is structured and methodical, preconceived to a certain point, and then realized in the process of making.

…

To Gormley, the body has a relation to the external space within which it exists as well as to the inner space it contains. And in a [1991] installation made for “Places with a Past,” an exhibition of site-specific art at Charleston, South Carolina, Gormley combined a series of works — Host, Field, Three Bodies, Learning to Think, Fruit and Cord — in order to explore that relationship. The Old City Jail, which contained and became part of the installation, could be described as having the shape of a body: the original rectangular structure is rather like a torso; its later octagonal addition, like a head. And in order to emphasize its parallels with his body cases, which are sometimes connected to the outside world through orifices, Gormley removed the boards and glazing that had sealed up the prison’s doors and windows. This allowed light and sound to enter the prison, to enliven what had hitherto been dark and dormant, and to engage time as an active element in the installation. In the artist’s words, “the building became a catalyst for reflection on liberty and incarceration.”

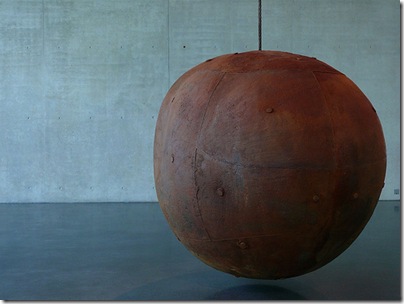

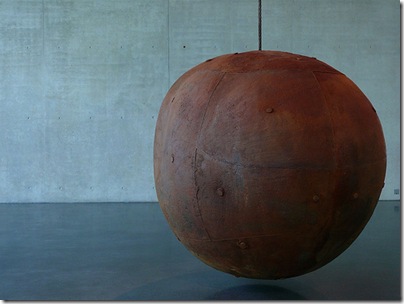

One the second floor, Field, a set of terracotta figurines, faced a similar vast space that contained only Three Bodies—large metal spheres, made of steel and air, which the aritst has described as “like celestial bodies fallen from the sky.”

Above Field was Learning to Think, five headless lead body cases that were suspended from the ceiling, in a contradictory evocation of both lynching and ascension. The corresponding space held Host, a room containing mud and sea water — “The surface of the earth described in Genesis…the unformed, the place of possibility, a place waiting for the seed,” according to Gormley.

In the octagonal extension, two related organic forms, Fruit, were hung on either side of a wall. Only one was visible at a time in order “to reconcile opposites not in terms of differentiation but by mirroring,” Hidden from view, and at the center of each sculpture, was a space once occupied by the artist’s own body, linked to the other side, though mouth and genitals, by steel pipes. The final piece was Cord, made of many tubes inside one another — a kind of umbilical lifeline between the “seen” and “unseen.”

In this installation, one of great richness and complexity, Gormley brought into play the full panoply of his ambition. Working with lead and clay, as well as with the four elements, Gormley alluded to physical and spiritual containment, body and mind, outer and inner worlds, feeling and thinking, birth and death, growth and decay. And if the contradictions inherent in  Learning to See give strength to the artist’s conception of inner vision, the dualities evoked by the installation at Charleston are subservient to a sense of passage towards expansiveness. The emotional depth of the work can be ascribed to its refusal to exclude either the particular or the universal: it encompasses both historical specificity and a sense of shared human experience. In formal terms, this is achieved by the undermining of the Modernist notion of the self-referential object. While each of the elements of the installation can be separately contemplated, they are most meaningful when perceived as parts of a larger whole. In that sense, they are like parts of a body.

Learning to See give strength to the artist’s conception of inner vision, the dualities evoked by the installation at Charleston are subservient to a sense of passage towards expansiveness. The emotional depth of the work can be ascribed to its refusal to exclude either the particular or the universal: it encompasses both historical specificity and a sense of shared human experience. In formal terms, this is achieved by the undermining of the Modernist notion of the self-referential object. While each of the elements of the installation can be separately contemplated, they are most meaningful when perceived as parts of a larger whole. In that sense, they are like parts of a body.

Learning to See give strength to the artist’s conception of inner vision, the dualities evoked by the installation at Charleston are subservient to a sense of passage towards expansiveness. The emotional depth of the work can be ascribed to its refusal to exclude either the particular or the universal: it encompasses both historical specificity and a sense of shared human experience. In formal terms, this is achieved by the undermining of the Modernist notion of the self-referential object. While each of the elements of the installation can be separately contemplated, they are most meaningful when perceived as parts of a larger whole. In that sense, they are like parts of a body.

Learning to See give strength to the artist’s conception of inner vision, the dualities evoked by the installation at Charleston are subservient to a sense of passage towards expansiveness. The emotional depth of the work can be ascribed to its refusal to exclude either the particular or the universal: it encompasses both historical specificity and a sense of shared human experience. In formal terms, this is achieved by the undermining of the Modernist notion of the self-referential object. While each of the elements of the installation can be separately contemplated, they are most meaningful when perceived as parts of a larger whole. In that sense, they are like parts of a body.  Just as the day could use another hour,

Just as the day could use another hour,

“I see nothing irrational about seeking the states of mind that lie at the core of many religions. Compassion, awe, devotion and feelings of oneness are surely among the most valuable experiences a person can have…Ecstasy, rapture, bliss, concentration, a sense of the sacred—I’m comfortable with all of that…I think all of that is indispensable and I think it’s frankly lost on much of the atheist community.”

“I see nothing irrational about seeking the states of mind that lie at the core of many religions. Compassion, awe, devotion and feelings of oneness are surely among the most valuable experiences a person can have…Ecstasy, rapture, bliss, concentration, a sense of the sacred—I’m comfortable with all of that…I think all of that is indispensable and I think it’s frankly lost on much of the atheist community.” In

In  This was, it turns out, a quaint scenario, grossly simplistic and deeply melodramatic. As the Internet proves every day, it isn’t some stern and monolithic Big Brother that we have to reckon with as we go about our daily lives, it’s a vast cohort of prankish Little Brothers equipped with devices that Orwell, writing 60 years ago, never dreamed of and who are loyal to no organized authority. The invasion of privacy — of others’ privacy but also our own, as we turn our lenses on ourselves in the quest for attention by any means — has been democratized.

This was, it turns out, a quaint scenario, grossly simplistic and deeply melodramatic. As the Internet proves every day, it isn’t some stern and monolithic Big Brother that we have to reckon with as we go about our daily lives, it’s a vast cohort of prankish Little Brothers equipped with devices that Orwell, writing 60 years ago, never dreamed of and who are loyal to no organized authority. The invasion of privacy — of others’ privacy but also our own, as we turn our lenses on ourselves in the quest for attention by any means — has been democratized. “More than ever, I have come to appreciate how deeply and passionately most of us live within ourselves. Our attachments are ferocious. Our loves overwhelm us, define us,

“More than ever, I have come to appreciate how deeply and passionately most of us live within ourselves. Our attachments are ferocious. Our loves overwhelm us, define us,

That’s the first step, but it’s not the razor’s edge. We’re still separate, but now we know it. How do we bring our separated life together? To walk the razor’s edge is to do that; we have once again to be what we basically are, which is seeing, touching, hearing, smelling; we have to experience whatever our life is, right this second. If we’re upset we have to experience being upset. If we’re frightened, we have to experience being frightened. If we’re jealous we have to experience being jealous. And such experiencing is physical; it has nothing to do with the thoughts going on about the upset.

That’s the first step, but it’s not the razor’s edge. We’re still separate, but now we know it. How do we bring our separated life together? To walk the razor’s edge is to do that; we have once again to be what we basically are, which is seeing, touching, hearing, smelling; we have to experience whatever our life is, right this second. If we’re upset we have to experience being upset. If we’re frightened, we have to experience being frightened. If we’re jealous we have to experience being jealous. And such experiencing is physical; it has nothing to do with the thoughts going on about the upset.

"Mindfulness is a practice of attentive yielding and accepting in the body, in the emotions, which gradually dissolves our futile root habit of conducting a kind of emotional lawsuit with everything that balks us or threatens us in any way. Energy previously blocked in controlling ourselves or wasted in negative, self-centered discharge becomes available for making appropriate and positive response (including warm, outgoing feelings) to situations we encounter."

"Mindfulness is a practice of attentive yielding and accepting in the body, in the emotions, which gradually dissolves our futile root habit of conducting a kind of emotional lawsuit with everything that balks us or threatens us in any way. Energy previously blocked in controlling ourselves or wasted in negative, self-centered discharge becomes available for making appropriate and positive response (including warm, outgoing feelings) to situations we encounter."

What does this have to do with our practice? Practice is about breaking our exclusive identification with ourselves. This process has sometimes been called purifying the mind. To “purify the mind” doesn’t mean that you become holy or other than you are; it means to strip away that which keeps a person—or furnace—from functioning best. The furnace functions best with hard coal. But unfortunately what we’re full of is soft coal. There’s a saying in the Bible: “He is like a refiner’s fire.” It’s a common analogy, found in other religions as well. To sit in meditation is to be in the middle of a refining fire. Eido Roshi said once, “This meditation hall is not a peaceful haven, but a furnace room for the combustion of our egoistic delusions.” A meditation hall is not a place for bliss and relaxation, but a furnace room for the combustion of our egoistic delusions. What tools do we need to use? Only one. We’ve all heard of it, yet we use it very seldom. It’s called attention.

What does this have to do with our practice? Practice is about breaking our exclusive identification with ourselves. This process has sometimes been called purifying the mind. To “purify the mind” doesn’t mean that you become holy or other than you are; it means to strip away that which keeps a person—or furnace—from functioning best. The furnace functions best with hard coal. But unfortunately what we’re full of is soft coal. There’s a saying in the Bible: “He is like a refiner’s fire.” It’s a common analogy, found in other religions as well. To sit in meditation is to be in the middle of a refining fire. Eido Roshi said once, “This meditation hall is not a peaceful haven, but a furnace room for the combustion of our egoistic delusions.” A meditation hall is not a place for bliss and relaxation, but a furnace room for the combustion of our egoistic delusions. What tools do we need to use? Only one. We’ve all heard of it, yet we use it very seldom. It’s called attention.  There’s a part of practice that I think is inherent in all different practices. The type of concentration, the familiarity, the intimacy that you get to whatever you’re practicing, whether it’s archery or Zen or music or how to make a perfect pancake. You won’t get there unless you get intimate with the subject. You only get there through practice. As you become more intimate, you know more about it, where you can say “This batter is too liquid or too solid or too warm too cold. It’ll act this way.” All that comes only through practice. It comes up often in conversations with my friends about how people go about life these days, that they’re really not willing to practice anything.

There’s a part of practice that I think is inherent in all different practices. The type of concentration, the familiarity, the intimacy that you get to whatever you’re practicing, whether it’s archery or Zen or music or how to make a perfect pancake. You won’t get there unless you get intimate with the subject. You only get there through practice. As you become more intimate, you know more about it, where you can say “This batter is too liquid or too solid or too warm too cold. It’ll act this way.” All that comes only through practice. It comes up often in conversations with my friends about how people go about life these days, that they’re really not willing to practice anything.  The other day we got to talking about jeans. There’s only one of the old fashioned wooden looms in America. I think it’s actually in Raleigh, North Carolina. All the other ones were shipped to Japan, and that’s in the ‘50s. And that’s where you get the superior denim because people are willing to make things by hand and become intimate with it. Whereas a lot of people in the United States or in Europe will just go, “I’d rather buy ten pairs at Walmart than buy one pair of really good jeans, even though the really good pair will probably outlast the ten pairs they buy at Walmart.” So, there’s a lack of that—you might say depth—that comes from not practicing, from not practicing a craft.

The other day we got to talking about jeans. There’s only one of the old fashioned wooden looms in America. I think it’s actually in Raleigh, North Carolina. All the other ones were shipped to Japan, and that’s in the ‘50s. And that’s where you get the superior denim because people are willing to make things by hand and become intimate with it. Whereas a lot of people in the United States or in Europe will just go, “I’d rather buy ten pairs at Walmart than buy one pair of really good jeans, even though the really good pair will probably outlast the ten pairs they buy at Walmart.” So, there’s a lack of that—you might say depth—that comes from not practicing, from not practicing a craft.

At any given moment, we have a limited amount of attention to spend. Just being clear about what we are noticing can begin to change ordinary experience in simple yet profound ways. Listening to music offers a compelling doorway into this perspective. When we focus on one or more aspects of listening, we strengthen our ability to concentrate. When we explore music as an opportunity to cultivate attention, we also strengthen the ability to hear the musicality within the ordinary sounds we encounter in daily life. With consistent practice over time, we can even begin to experience the sense of wonder which sparks the human impulse to create music in the first place.

At any given moment, we have a limited amount of attention to spend. Just being clear about what we are noticing can begin to change ordinary experience in simple yet profound ways. Listening to music offers a compelling doorway into this perspective. When we focus on one or more aspects of listening, we strengthen our ability to concentrate. When we explore music as an opportunity to cultivate attention, we also strengthen the ability to hear the musicality within the ordinary sounds we encounter in daily life. With consistent practice over time, we can even begin to experience the sense of wonder which sparks the human impulse to create music in the first place. "The goal of becoming a better person is within the reach of us all, at every moment. The tool for emerging from the primitive yoke of conditioned responses to the tangible freedom of the conscious life lies just behind our brow. We need only invoke the power of mindful awareness in any action of body, speech, or mind to elevate that action from the unconscious reflex of a trained creature to the awakened choice of a human being who is guided to a higher life by wisdom."

"The goal of becoming a better person is within the reach of us all, at every moment. The tool for emerging from the primitive yoke of conditioned responses to the tangible freedom of the conscious life lies just behind our brow. We need only invoke the power of mindful awareness in any action of body, speech, or mind to elevate that action from the unconscious reflex of a trained creature to the awakened choice of a human being who is guided to a higher life by wisdom."