Excerpts from “Demonstrations, Hopes, and Dreams,” Being, Feb. 10, 2011:

Dr. Scott Atran: If you take these polls like the Gallup and Pew polls, you find that about 7 percent of the Muslim world has some sympathy for bin Laden. That's about 100 million people out of 1.3 or 1.4 billion Muslims in the world. But then if you look who actually is willing to do something violent, you find that it's an extremely, extremely small number of people. But when you look at of those thousands out of the 100 million who actually do anything, you find that the greatest predictor has nothing to do with religion.

The greatest predictor is whether they belong to a soccer club or some action-oriented group of friends. In fact, almost none of them had any religious education whatsoever. They're all born again, sort of between the ages of 18 and 22. So if it's not religious inculcation, if it's not religious training, if it's not even religious tradition, what could it possibly be? And again, it's first of all who your friends are. That's the greatest predictor of everything. Then there's a sort of geopolitical aspect to it. I mean, people talk about a clash of civilizations. I think that's dead wrong. There's a crash of territorial cultures across the world.

Krista Tippett: Yeah. I want you to talk about that. I think that's a very intriguing distinction you draw that it's not a clash of civilizations, but you've also said a crash of civilizations. So tell me what you're describing there.

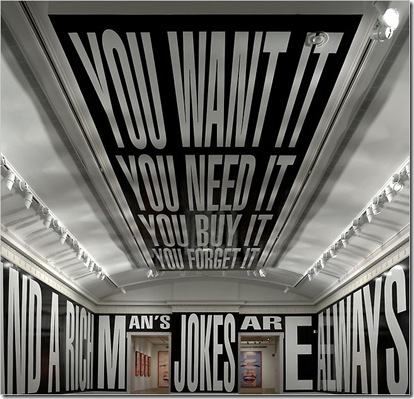

Dr. Atran: Well, globalization, of course, has provided access to large masses of humanity to a better standard of living, better health, better education. But it has also left in its wake many traditional societies that are falling apart, that just can't compete. So what you have is young people especially sort of flailing around looking for a sense of social identity. These traditional territorial cultures and their influence disappears and it's happening across all of this sort of middle attitudes of Eurasia and they're trying to hook up with one another peer to peer.

And this is paralleling another new development in history of humanity and that is this massive media-driven global political awakening where, again, for the first time in human history, you've got someone in New Guinea who can see the same images as someone in the middle of the Amazon. And so you've got these young people paradoxically focusing in on a smaller and smaller bandwidth in this sort of global media trying to hook up with one another and make friends and give themselves a sense of significance. And the Jihad comes along.

I mean, the Jihad — you know, I interviewed this guy in prison in France who wanted to blow up the American Embassy and I asked him, "Why did you want to do this?" and he says to me, "Well, I was walking along the street one day and someone spit at my sister and called her sale Arabe, a dirty Arab, and I just couldn't take it anymore and I realized that this injustice would never leave French society or Western society, so I joined the Jihad." I said, "Yeah, but that has been going on for years." And he goes, "Yes, but there was no Jihad before."

So it's a sort of receptacle. You find it's especially appealing to young people in transitional stages in their lives — immigrants, students, people in search of jobs or mates and between jobs and mates, and it gives a sense of empowerment that their own societies certainly don't. I mean, the message of the Jihad is, look, you, any of you, any of you out there, you too can cut off the head of Goliath with a paper cutter. That's what we did. We changed the world with paper cutters. That's all you need. All you need is will and truth and meaning, and you will correct injustice in the world and you'll be heroic and you'll have the greatest adventure of your lives. That's surely powerful.

* * * * *

Ms. Tippett: You know, at the beginning of your book, which is called Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of Terrorists, right before the table of contents, you have this absolutely beautiful picture of children. It looks like they're either coming out of school or going to school. They're beautiful children. It's kind of a heartbreaking picture in a lovely way.

Then I read underneath that it's a school that you mentioned early on. You say, school's out at this school in Morocco from which five of the seven plotters of the Madrid train bombing who blew themselves up attended, as did several volunteers for martyrdom in Iraq. Tell me why you put that picture at the beginning of your book and what you would like a reader or someone coming to these ideas to see in that picture.

Dr. Atran: Because those are the terrorists. Those are those who would be terrorists or would be us or our friends. And it is up to us and how we deal with the political world and the hopes and dreams that emerge in their own societies that will decide whether they go one way or the other. It's not, again, the fact that there are good or bad ideologies out there. It's not the fact of lack of presence of economic opportunities per se. It's whether there are paths in life that can lead them to something that's more congenial to the way we live in the world. I think we have many things to offer, but not in the way we're doing it.

I mean, I'm reminded very much of Maximilien Robespierre's statement to the Jacobin Club in the French Revolution, a statement he promptly forgot, which was, "No one loves armed missionaries." No one loves armed missionaries. No one loves the fact that we have troops out there in the world trying to preserve or push democracy or whatever. As Jefferson said, "The way we're going to change the world is by our example. Never, never can it be by the sword." Now sometimes you have to fight things. When people want to kill you, when people want to blow you up, then you have to fight them. There may be at the time no opportunity.

But that's not the case with the vast majority of people who could possibly become tomorrow's terrorists. That's where the fight for the world will be. It will be in the next generation of these young people, the ones caught between should we go the path of happiness as martyrdom or should we go to the path of yes, we can. They're both very enticing paths. I think one has a lot more to offer, but we have to show them it has more to offer, and we have to show them now. And that's what they're asking for right now.

Listen to the entire conversation on Being…

Study subjects sat further away from someone of another race when the train station was a mess.

Study subjects sat further away from someone of another race when the train station was a mess. Krista Tippett (host): I'm utterly intrigued just by the way you describe your passion, your interest and concern, that you study this objective side of our encounters with technologies, that I'm concerned with— the human meaning of the objects of our lives. And just as we start, I wanted to ask you a kind of question I ask everyone, which is, was there a spiritual background to your childhood?

Krista Tippett (host): I'm utterly intrigued just by the way you describe your passion, your interest and concern, that you study this objective side of our encounters with technologies, that I'm concerned with— the human meaning of the objects of our lives. And just as we start, I wanted to ask you a kind of question I ask everyone, which is, was there a spiritual background to your childhood?

I have enough data from children who're going through this experience to know that it's a terrible moment for them. It's on the playground. Very bad when your child's on the jungle gym and is desperately trying to have you look at them, for them to be taking hands off the jungle gym to try to get your attention — accident time. I mean, be in the park. Be in the park with them. Spend less time there, but make it a space. Make it a moment. These are important moments.

I have enough data from children who're going through this experience to know that it's a terrible moment for them. It's on the playground. Very bad when your child's on the jungle gym and is desperately trying to have you look at them, for them to be taking hands off the jungle gym to try to get your attention — accident time. I mean, be in the park. Be in the park with them. Spend less time there, but make it a space. Make it a moment. These are important moments.

liberate individuals from repressive social constraints didn’t produce a flowering of freedom; it weakened families, increased out-of-wedlock births and turned neighbors into strangers. In Britain, you get a country with rising crime, and, as a result, four million security cameras.

liberate individuals from repressive social constraints didn’t produce a flowering of freedom; it weakened families, increased out-of-wedlock births and turned neighbors into strangers. In Britain, you get a country with rising crime, and, as a result, four million security cameras. Originally, Dharma, meaning all traditional spirituality, in this case…All the great spiritual traditions have appeared in a world where human culture, because of technological reasons, first of all, and because of limited number of humans at the time, did not have the power to threaten the world. To threaten the natural world, to threaten the limits of the resources in the world, to threaten each other. Many cultures existed in spatial isolation, or distanced enough from each other to feel safe, which is now an impossibility. We can’t even plan to achieve that in the future because we’re going in the opposite direction. We’re not just closing on each other, we’re mixing up to an incredible degree all over the world.

Originally, Dharma, meaning all traditional spirituality, in this case…All the great spiritual traditions have appeared in a world where human culture, because of technological reasons, first of all, and because of limited number of humans at the time, did not have the power to threaten the world. To threaten the natural world, to threaten the limits of the resources in the world, to threaten each other. Many cultures existed in spatial isolation, or distanced enough from each other to feel safe, which is now an impossibility. We can’t even plan to achieve that in the future because we’re going in the opposite direction. We’re not just closing on each other, we’re mixing up to an incredible degree all over the world. The most fundamental sources of self-understanding are found at the level of story. To put the thesis even more directly: if we are to respond effectively to the global problematique then we must attend to our stories, for in the story of a culture we find its most profound expression of wisdom.

The most fundamental sources of self-understanding are found at the level of story. To put the thesis even more directly: if we are to respond effectively to the global problematique then we must attend to our stories, for in the story of a culture we find its most profound expression of wisdom.